Data-Driven Investment for Nature-Based Solutions

Data-Driven Investment for Nature-Based Solutions

Investors are increasingly seeking opportunities to invest their money in ways that align with their environmental and social values.

Mangroves are one of the promising new asset classes being explored, delivering quadruple benefits in terms of mitigation (carbon), resilience, biodiversity and livelihoods.

The economic value of mangroves in Bangladesh is estimated to be billions of dollars per year. This is a topic high on the agenda both at local level and internationally, with initiatives like the Mangrove Breakthrough aiming to mobilise significant action to protect and restore mangroves.

In order to make informed investment decisions, both public and private financial institutions need information on the social and environmental benefits of mangrove investments, information to assess the most suitable restoration and protection projects for a location to address drivers of loss and the costs, as well as the potential to generate financial returns and mitigate risks.

Global datasets bring new opportunities for both local communities, governments and investors to identify opportunities and structure financing that can deliver major capital for restoration.

Mangroves are unique trees that grow where land meets the sea. Their complex roots and ability to handle saltwater have adapted them to life in stormy coastal environments.

Mangroves are nature's protection walls that shield people from severe storms, regulate flood, filtrate pollution, keep the coastlines intact, reduce soil erosion, maintain cooler temperatures and play a key role in sustaining coastal health.

But the importance of mangroves goes even further. Homes and breeding grounds for various species of plants and animals, coastal communities rely on them for food and livelihoods.

Mangroves not only provide local benefits, but also play a role in global climate regulation by absorbing tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. These ecosystem services make mangrove forests a valuable nature-based solution (NBS).

The Sundarbans

The largest and one of the most important mangrove forests in the world - The Sundarbans, is in the delta of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers in the Bay of Bengal.

The Sundarbans is a transboundary mangrove forest shared by Bangladesh and India, it covers an area of over 10,000 square kilometres and is home to a wide range of biodiversity, including the Royal Bengal tiger, spotted deer, saltwater crocodile, and myriad bird species leading it to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

60% of the Sundarbans mangrove forest is in Bangladesh, making Bangladesh one of the priority country for mangrove restoration and protection projects.

1/4

Population

>1000

People p/ km²

35

Million people

Live in the coastal regions of Bangladesh

Bangladesh: Climate Risk.

Bangladesh is a low-lying coastal country with over 700 kilometres of coastline. This makes it particularly vulnerable to climate hazards, such as sea level rise, storm surges, and cyclones. These hazards are already causing significant damage and displacement and are expected to worsen due to climate change.

Over 35 million people live in the coastal zone of Bangladesh, which is about one-quarter of the country's population. These coastal communities are vulnerable to coastal hazards due to their low elevation, poor infrastructure, and reliance on agriculture and fishing.

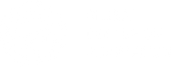

Figure 2 depicts the scope and severity of coastal flood events in Bangladesh that have a 2% annual occurrence probability (equivalent to a 1-in-50-year chance). It reveals that over 13.5 million people are at potential risk of life-threatening impacts from these floods, with water depths ranging from 1 meter to over 5 meters. Moreover, in some of the affected areas, the population density exceeds 1,000 people per square kilometre.

The economy along Bangladesh's coastline largely depends on agriculture and fisheries, sectors that face risks from coastal hazards including cyclones, storm surges, and the encroachment of saltwater.

Flooding frequently submerges vast tracts of agricultural land, with peak events impacting millions of acres. Beyond the direct inundation, the long-term incursion of salinity from storm surges and the gradual rise of sea levels undermines soil fertility, jeopardising traditional agricultural practices.

The economic toll of crop destruction due to these factors is substantial, often exceeding hundreds of millions of dollars, and this has a profound effect on both the national economic framework and the subsistence of local farming communities.

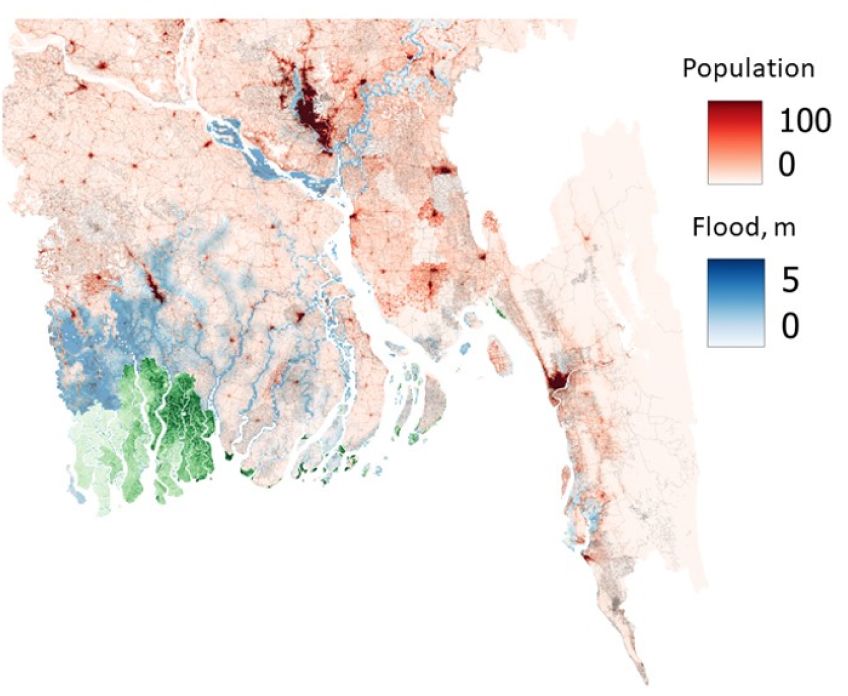

Due to climate change, most climate-related hazards will increase in frequency and/or intensity. The most critical climate change-induced hazards in Bangladesh are floods, sea-level rise, salinity, cyclonic storm surges, droughts, extreme heat waves, extreme cold, riverbank erosion, lightning, landslides, higher sea surface temperature and ocean acidification.

For example, future 50 cm sea-level rise combined with a cyclonic storm surge could potentially inundate large parts (11-12%) of the coastal area of Bangladesh and push salinity further inwards.

According to the National Adaptation Plan of Bangladesh (2023-2050), the current rate of annual loss to gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately 1.3 percent due to climate-induced disasters may rise to 2 % by 2050 and over 9 percent by 2100 under extreme scenarios. The number of internal climate migrants may reach 19.9 million by 2050, comprising half of those in the entire South Asian region

Around 22,000 km2 of the nation (or 17% of the land area) can be destroyed by a one-meter sea level rise, devastatingly affecting the health and safety of nearly 17 million people, biodiversity, and livelihoods like agriculture, forestry, and fishing.

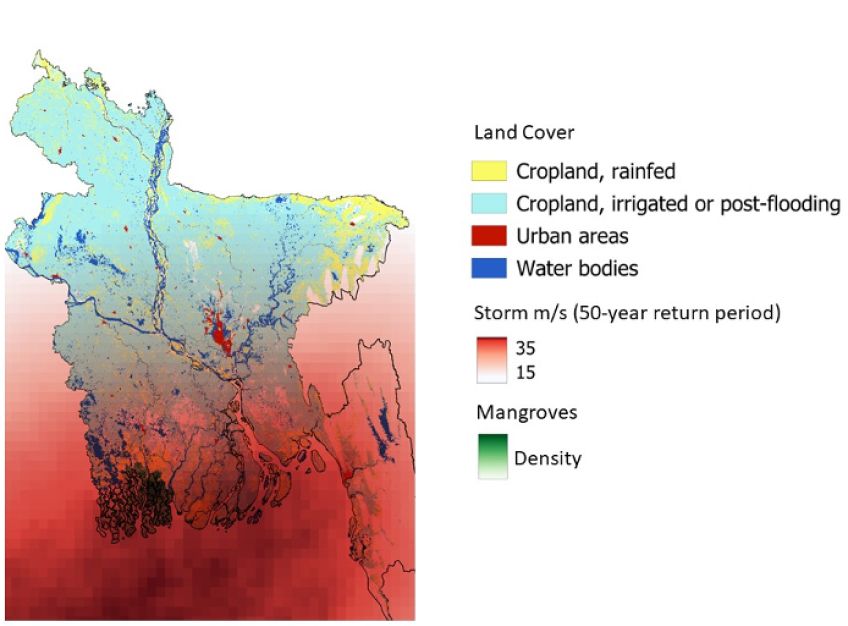

The coastal zone of Bangladesh is around 32% of the country's total land area and accounts for 30% of its cultivable land. It supports a substantial population, with a density of approximately 743 people per square kilometer in certain areas. These areas contribute significantly to country’s economy. Despite this, more than a third of the coastal rural population live in poverty. This makes it difficult for people to afford to build resilient homes and businesses, and to recover from disasters.

Figure 3 Coastal Bangladesh. Administrative regions with poverty higher than 40%.

Sundarbans, Bagerhat, Bangladesh | Image by Mamun Srizon, UnSplash

Empowering Green Infrastructure

Mangroves as a nature-based solution

Climatic and environmental hazards significantly impact agricultural land, infrastructure, and settlements. The mangroves act as natural barriers. They can help to reduce the risk of flooding, erosion, and storm surge damage.

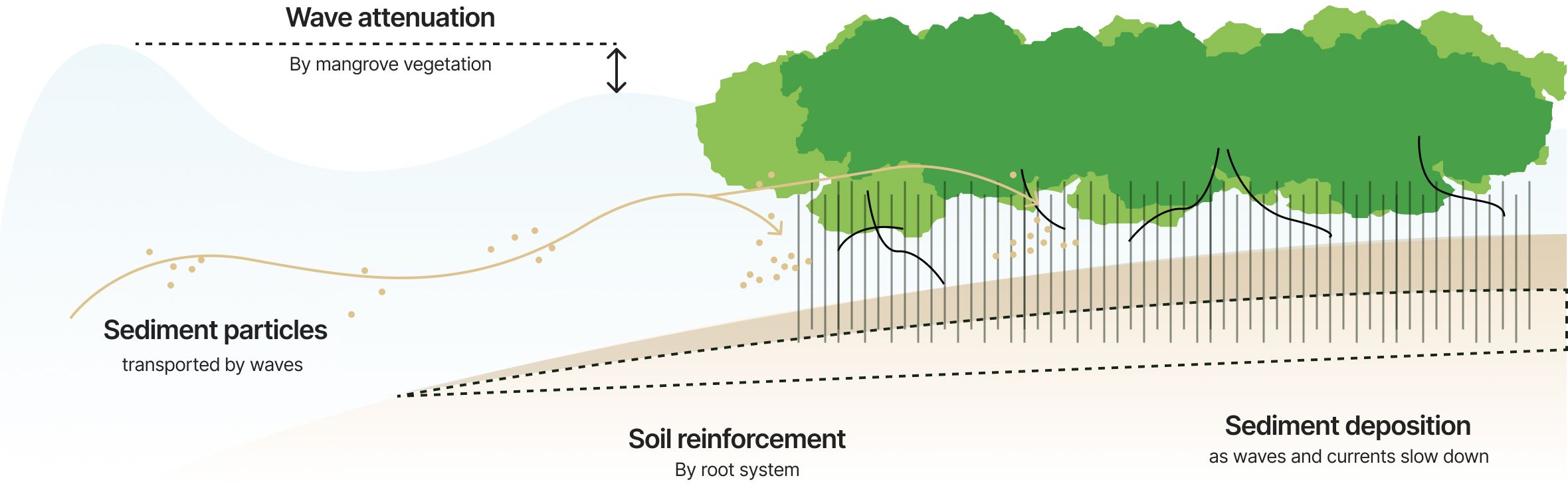

Mangroves have the ability to reduce the height of wind and swell waves over relatively short distances: wave height can be reduced by between 13 and 66% over 100 m of mangroves.

Previous studies in Bangladesh showed a significant reduction in water flow velocity (29-92%) and a moderate reduction in surge height (4-16.5 cm).

The level of protection provided by mangroves varies depending on the density of the forest and the species present. For example, a wider and denser mangrove forest will generally provide more protection than a narrower forest strip. Some mangrove species also have aerial roots that are particularly effective at dissipating wave energy.

Based on the average global benefits of mangrove flood protection (approx. 15,000 USD/ha), the annual flood protection benefit of the Sundarbans mangroves to Bangladesh could be scaled up to 10 billion USD.

Figure 4 Coastal protection by mangroves 1

Given its topography, large parts of Bangladesh are susceptible to tidal flooding. Mangroves help stabilise the coastline and prevent erosion by binding the soil together with their extensive root systems.

Recent figures indicate that the economic value of agricultural land stabilisation due to Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) interventions in the mangrove plantation program along the Bangladesh coast is estimated at 18,837 million USD.

A significant portion of Bangladesh's population depends on the mangrove ecosystem for their livelihood. This includes fishing, honey collection, and wood gathering. Residents living in or adjacent to the Sundarbans heavily rely on the forest for their essential needs, such as energy, construction materials for dwellings, boats, furniture, and fishing gear, as well as herbal medicines and various goods for trade.

A considerable segment of the population living near the coastal mangrove forests in Bangladesh relies on these ecosystems for their livelihoods. Crab harvesting is a primary source of income for about a quarter of these individuals. In addition, other community members engage in collecting nipa palm, honey, and timber, though these activities constitute smaller proportions of the direct dependency, ranging between 6% and 9% for each activity.

The mangrove forests are also vital for local fishermen and shrimp fry gatherers, with these activities supporting nearly half of the population that depends directly on the forest. Those with indirect reliance on the mangroves have varied occupations, with manual labour being the most common, followed by agriculture, shrimp aquaculture, and trade. These activities support 21% to 17% of the indirect dependents respectively, illustrating the broad socioeconomic importance of mangrove ecosystems in the region.

Figure 5 Mangrove Forest. One of the plantations to the East of Sundarbans.

As Bangladesh aims to contribute to global climate solutions, maintaining its mangrove forests is a natural strategy.

Mangroves are effective at storing carbon, which can help in efforts to combat climate change. For example, since their establishment in 1966, mangrove plantations to the east of the Sundarbans have become significant carbon sinks (Figure 5).

So far, planted trees alone have absorbed about 76,607 tons of carbon each year, and the soil has taken in another 37,542 tons, adding up to 114,149 tons of carbon trapped every year. If these plantations keep growing at this rate, by 2030 they will have captured an extra 664,850 tons of carbon.

This would help Bangladesh achieve 4.4% of its target to cut down on the gases that warm the planet, a target set in the country's own plan for tackling climate change10. But these vital mangrove forests are now under threat from rising sea levels, stronger storms, and damage from local human activities (as shown in Figure 5).

The role of data

The Global Centre on Adaptation is collaborating with teams from the University of Oxford, including the Oxford Programme for Sustainable Infrastructure Systems, the Resilience & Development Programme, and the Nature-based Solutions Initiative, to explore global tools for addressing key data gaps and unlocking capital for investment in NBS.

These tools aim to determine the scale at which NBS can protect infrastructure from climate change impacts, quantify the value of existing nature-based assets and use this information to identify and evaluate NBS investment options.

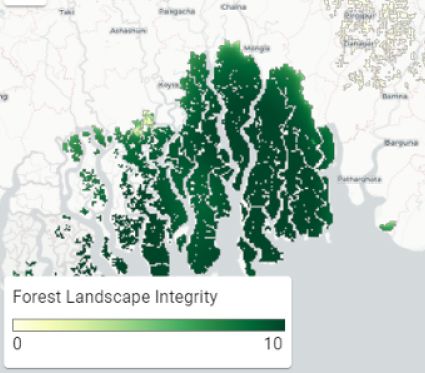

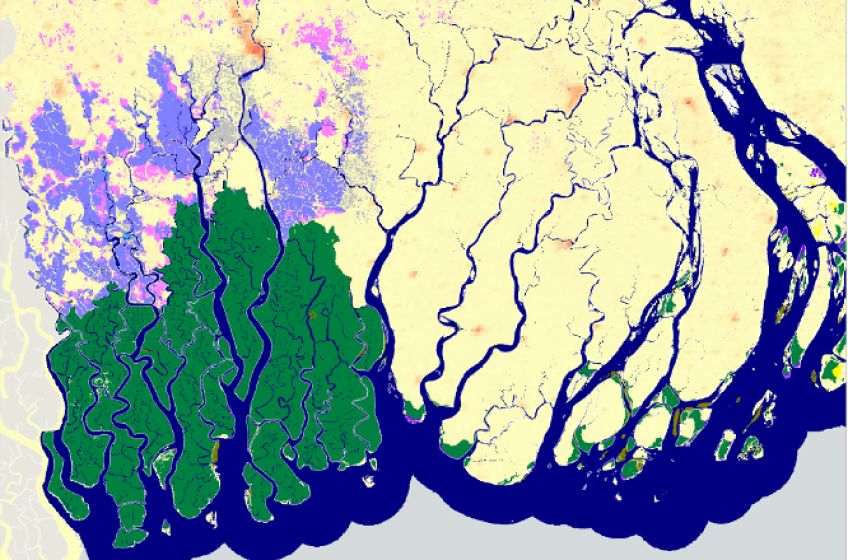

The project draws on the information about the location, size, and condition of the mangrove forest, as well as current and future threats facing the mangroves. One of the objectives is to develop a geospatial tool to support location and prioritisation of nature-based solutions to improve infrastructure resilience in Bangladesh using peer-reviewed research and publicly available datasets.

As the project scales up to global, the team are planning to add open-data layers and analysis to the GRI Risk Viewer tool.

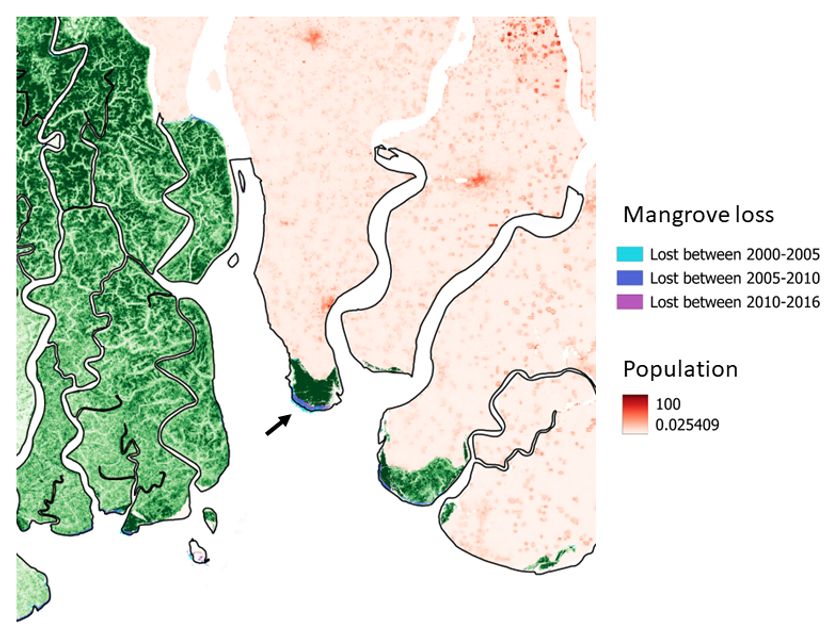

What is clear is that the Sundarbans have been facing significant degradation over the years due to: deforestation, infrastructure development, shrimp farming, pollution, overfishing and the collection of honey and timber beyond sustainable levels, rising sea levels, storms, salinity changes and lack of effective land management.

One of the biggest challenges is salinity, which results from the reduced flows of freshwater from upstream. Figure 7 shows loss of mangroves due to land-use change and various other drivers.

Figure 6 Forest landscape integrity. Tool/Data: GRII

Figure 7 Global Mangrove Change, 1999-2021. Mangrove, pond and wetland landcover change and persistence (1999-2020).

The GRI Risk Viewer

What does this mean for investors?

So, as an investor, how do you use this information to make decisions? We’ve detailed 3 steps below:

01 Mapping the types of projects

Firstly, to map the types of projects likely to be viable and beneficial in different locations, and not, and where wider drivers may need to be address, e.g., tackling salinity.

Such projects can involve community-based reforestation efforts, as well as efforts to preserve existing mangrove forests.

02 Understanding the commercial returns

Secondly, to get a sense of the potential commercial returns, including through carbon markets.

Carbon financing has the potential to support the conservation of roughly one-fifth of the world's mangrove ecosystems, which cover an area of 2.6 million hectares.

A significant portion of these areas, between 1.1 and 1.3 million hectares, could sustain their conservation efforts financially for three decades if carbon is valued at $5 to $9.4 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent.

Such an initiative is expected to sequester about 29.8 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent annually, potentially generating an annual return of approximately $3.7 billion

03 Estimate the benefits to the wider society

And thirdly, to estimate the wider benefits to society and nature that while currently more difficult to monetise can be significant and in some cases justify a risk premium reduction from investors.

For example, the annual economic contribution of tourism to the Sundarbans mangroves is estimated at USD 53 million. The mangrove ecosystem services, in general, are known to generate significant benefits and well-being.

The Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem contributes significantly to the local economy through fishing activities. Monetary estimates indicate that households can derive considerable income annually from capture fishery, averaging USD 976 per hectare.

Mangroves are crucial for coastal protection, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration, making their restoration vital for ecological resilience and the well-being of adjacent human communities.

The harnessing of data is instrumental in advancing mangrove restoration, ultimately contributing to both environmental protection and the promotion of sustainable development.

Written with support from